![]()

The Words of the Johnson Family

|

|

The Words of the Johnson Family |

The

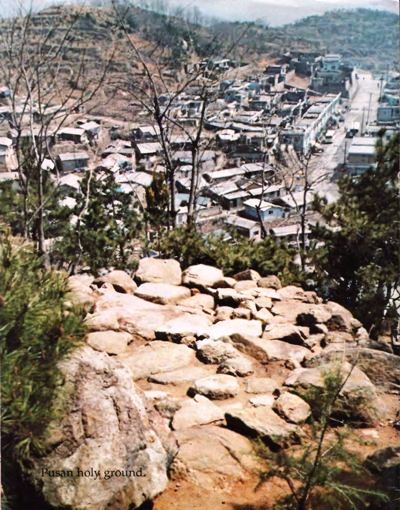

hill that Father lived on in Pusan

Pusan was one of the only cities not ravaged by the Korean War, yet it served as a nerve center and a reservoir for everything occurring during these years from 1950 into 1953 (the time of Father's ministry there).

The finest natural harbor lies at the southern tip of the peninsula, where the climate is mild, and where the shallow, meandering Naktong River meets the sea, lies Pusan. In the misty distance the Japanese island of Tsushima can sometimes be seen. Lofty peaks rise beyond the pine-clad hills. Near the ports stand rice-cleaning mills, breweries, textile mills for weaving cotton and silks. Near Pier One is the fish market. Toward suburban villages are pottery kilns, where rows of rich-red clay wares, bowls and pots for storing kimchi are laid to dry in the sun. Fall and spring are times of the big markets, when Koreans from all over the peninsula gathered to shop and barter for tobacco, woven mats, sandals, herbs, cooking pots and supplies for the season. Within an easy day's journey lie resorts with hot springs and mineral baths, and the observatory built centuries ago to study the stars at Keishu. Nearby there is Kyung-ju, the capital of the Silla Dynasty with ruins of temples and palaces to explore.

Pusan had the advantage of being built up with Western technology by the Japanese, with streets laid out in grid pattern, an efficient system of trams linking commercial, industrial, residential and outlying areas. Two fine rail lines connected Pusan with other urban centers. There were modern port facilities, electricity and telephones.

After World War II Pusan experienced rapid growth with migration of young people from countryside into cities, and tens of thousands of Koreans repatriated from Japan. The economy was recovering, with Koreans being quickly trained to handle finances, politics, and management. For the first time since independence, Korea had surplus rice for export, and the newly organized Bank of Korea had just opened for business when unexpectedly the Korean War began June 25, 1950.

The significance of Pusan, her ports and connection to Japan (now occupied by American forces under General MacArthur) became evident. Quickly the United Nations responded to the emergency and troops were rushed from Japan to Pusan. The line of defense held by General Walker's combined UN and ROK (Republic of Korea) troops was called the Pusan Perimeter. Everything north of this vacillating battle line was held by the enemy. South Koreans fled at bayonet-point before the advancing troops, seeking safety in Pusan, but at the same time clogging narrow roads flanked by deep irrigation ditches, and greatly interfering with the war effort. North Korean guerrillas, in their mustard-yellow uniforms hidden under loose civilian clothes, banded and raided at night, attacking from the rear, until the UN Command enforced the order that any civilian moving at night would be shot on sight.

With General MacArthur's miraculous landing at Inchon September 15, the war zone was quickly pushed north above the 38th parallel by October, 1950. Hungnam was liberated, also Pyongyang and all the hills between, by ROK's and UN troops. For three weeks there was an uncanny silence around Pyongyang. The North Koreans strangely stopped fighting. Syngman Rhee declared, "We will wash our swords in the Yalu River," as the ROK's confidently pushed their victory to Manchuria. Under the cover of smoke of mysterious forest fires, the Red Chinese had crossed into Korea, and on October 25, 1950 they destroyed the advancing ROK army.

The United Nations Command decided to pull back. Seeing the new enemy swarming over Pyongyang, they realized they needed a defensible position, which was not possible on the muddy trails and frozen hills of North Korea. The retreat back toward Seoul in no way meant a reluctance to fight, or a surrender, to the men who ordered it. It meant that we would be the ones who choose where the decisive stand would be; not the enemy! South near Seoul was the only appropriate place, where the geography was such that enemy forces would be funneled through a narrow pass, flanked on both sides by hills standing as natural fortresses of defense. Here the UN Command held off a million Red Chinese and brought about a stalemate in the war. North Koreans held most of North Korea while UN troops fought on hill after hill to push the enemy back again.

During January 1951 refugees from North Korea were pouring south in zero-degree weather, clogging bridges and mountain trails like a river of fear. Already 60 tent camps established for South Korean refugees outside Pusan were desperately inadequate. Over 91,000 more refugees had been transported on ships from Hungnam harbor, so now Koje Island near Pusan became a reception center for over one million refugees. Here also would be compounds for 130,000 captured prisoners too, both North Korean and Red Chinese, who collected there by mid-1951.

Fuels, tanks, weapons, ammunition, rice, vital supplies from U.S. Army bases in Japan came through the ports of Pusan. Korean laborers transported ammunition and foods from ships to battle zones, and back again. The government had evacuated from Seoul for the second time December 31, 1950 with banking, broadcasting and civic matters reestablished in Pusan. Politics raged in Pusan as rival patriots all influenced by differing ideologies during their years in exile competed for power and sought to remake South Korean government according to their ideals.

At the beginning of the war North Korean soldiers had distributed vast sums of money plundered from the North, and counterfeit "Red Notes" printed from stolen plates. Their intention was to break the economy of the South. Quickly the Bank of Korea forced everyone to exchange old money for new Korean-style won notes, and three and a half times the amount of currency circulated legally before the war was collected and destroyed. Inflation means there is lots of money with little value, thus foreign credit relations will be cut as fatally as a jugular vein. "Balance the books," American advisors demanded of South Koreans. "To win the war you must control your economy!" They were fighting on two fronts: they had to win the shooting war and build the nation at the same time. "Fight and Build" would become the motto for victory.

By the end of January 1951, supplies of food were exhausted, and hoarding began, causing unexpected draining of key foods and supplies, causing an artificial market situation, causing more panic, more hoarding, more deficits, more fear. Smuggling, crime, and black markets all thrived. The American G.I.'s always had money, and refugees sought ways to serve them in exchange for it. Drafting young men was enforced. As war continued, every man between ages 17 and 40 was conscripted, sometimes with no formalities, just grabbing them off the street. This wasn't too different from methods of North Korea, but this was a time of crisis. Truce talks at Panmunjom meant that the war of words was heating up.

Prison riots began, and by May 1952 President Rhee declared martial law for security reasons, outlawing the cutting of trees for cooking fuel. The people were dismayed. President Rhee announced a war lottery. Money in the hands of refugees did nothing for the country; but this "potential capital" would be a crucial factor in rebuilding Korea, by channeling money through the bank into the hands of investors and businessmen who could make new starts in production and commerce.

Only cheap, foul-smelling sulphurous fuels were available, but smoke from tall industrial smokestacks along the Pusan harbors stood as silent testimony that production continued, the nation was progressing and life went on. Refugees had little heat in winter, but even the sight of smoke could bring a bitter-sweet reminder of hope.

President Rhee began patriotic programs of reforesting the nation, new national holidays commemorating the creation of Hangul language and the founding of Korea by legendary Tangun.

Truce talks finally called for ceasefire in July of 1953. The war was never officially ended, no peace treaty was ever signed, and it was never even a declared war; but to those who fought there, it went down in history as "the %, ar couldn't win, the war we couldn't lose, the war we couldn't quit." The government returned to Seoul. Prisoners were exchanged. And gradually Koreans faced the truth that they would remain a divided nation. Day by day hope returned and many Koreans picked up the pieces of their own divided lives and returned to their homes in the countryside or to Seoul.