5 Logic

Logic is the study of laws and forms of thinking. Formal logic, started by Aristotle, dealt with universal laws and forms of thinking, which are variously different in content, while dialectical logic especially that proposed by Hegel and Marx, dealt with the law and forms of the development of nature and thinking.

It is my intention in this chapter to discuss and critique the various system of logic and to present Unification logic, which is a system of logic derived from the Unification Principle.

I. Traditional Logic

A. Formal Logic

1. Basic Principles of Thinking

The basic laws of valid thinking, in traditional formal logic, are four principle , as follows:

- The principle of identity.

- The principle of contradiction.

- The principle of excluded middle.

- The principle of sufficient reason.

The principle of identity, which is expressed in the form “A is A”, corresponds to the identity-maintaining character of the existing being in Unification Thought. The principle of contradiction, which is expressed in the form “A is not non-A” is a negative way of expressing the (affirmative) principle of identity, as we can see by comparing the two propositions: “A is a flower”, and “A is not a non-flower”. These are supposedly the basic laws by which man thinks.

The principle of excluded middle, saying that “A is either B or non-B”, is the principle of alternative judgments, which we often use in thinking.

The principle of sufficient reason established by Leibniz says that all thinking has a reason, and there is no thinking without a reason. When applied to phenomena, we get the proposition, “Every phenomenon has a cause”; in other words, we get the law of cause and effect. Thus, reason (grounds) and conclusion in the thinking process correspond to cause and effect in the natural world. There are many other laws and principles, but they are derived from the four principles stated above, according to traditional logic.

2. Concept

Concept is a representation of the common properties abstracted from a group of individuals. A concept may be “generic” or “specific”. Let us think about the series, “living being, animal, vertebrate, mammal, etc.” Living beings have life. Besides life, animals have a sensory system (instinct), and vertebrates have also a backbone. Besides having life, instinct, and backbone, mammals are lactational. Finally, man has all these attributes as well as reason. The attributes that each concept contains are called connotation (intension). The class of things to which a concept is applicable is called extension. As examples of extension, ‘living being’ includes plants and animals; ‘animal’ includes vertebrates and invertebrates; ‘vertebrate’ includes reptiles and mammals; ‘mammal’ includes anthropoid apes and men; ‘man’ includes Peter, Mary, James, and so on.

Of two concepts, the one with broader connotation and narrower extension is called the specific concept (subordinate concept), whereas the one with narrower connotation and broader extension is called generic concept (superordinate concept). The concept ‘man’, for example, is specific, and the concept ‘mammal’ is generic, comparatively speaking. Similarly, the concepts of ‘vertebrate’, ‘coelenterate’, and ‘echinoderm’ are specific, when compared with the concept of ‘animal’. Furthermore, even the concepts of ‘animal’ and ‘plant’ are specific, when compared with the concept of ‘living being'.

Following along these lines, we reach the highest generic concept, which is ‘existence’. Under this concept we have ‘matter’ and “spirit’. ‘Matter’ is the highest concept in natural science, which usually deals solely with material processes and existence. Under the concept of ‘matter’, we have ‘living being’ and “inorganic matter’. Under ‘living being’, we have ‘animal’ and “plant’, and so forth.

The highest generic concept is called category. Each philosopher has his own category, according to his system of thought. Aristotle, Kant, and Marx, for instance, have their own categories. Unification Thought, also, has its own category, based on the concepts of Quadruple Base and give-and-take action. (See Ch. 4, “Epistemology.”)

3. Judgment

Judgment is the determination of the relationship between two concepts. A judgment consists of subject, predicate and copula, which brings the subject and the predicate into a relationship. When it is expressed with language, a judgment is called a proposition. There are many forms in judgment. Kant has four of them: the forms of quantity, quality, relation, and modality. Each of these forms has three components, making twelve judgment forms, which are often quoted as representative forms of formal logic.

4. Inference

Inference is a way of thinking with which a new judgment (conclusion) is drawn from known judgments (premises). The main forms of inference are mediate inference, which has more than two premises, and immediate inference, which has only one premise. A syllogism is a type of mediate inference that contains two premises, as we can see in the following example:

- All men die

- Socrates is a man

- Therefore Socrates will die

This is a three-staged process: (1) the major premise (which contains the predicate of the conclusion); (2) the minor premise (which contains the subject of the conclusion); and (3) the conclusion.

Immediate inference, however, has only one premise, from which the conclusion is directly derived. From the premise, “All Koreans are honest,” one can conclude directly that “Some Koreans are honest.”

Aoother kind of inference is analogical inference. Suppose ‘A’ and ‘B’ have the elements a, b, c, d, and e. ‘A’ has also the element ‘f’; thus by analogical inference we say that ‘B’, also may have ‘f’. Let us suppose that ‘A’ represents the earth and ‘B’, another planet. Both contain ‘a’ (atmosphere), ‘b’ (existence of water), ‘c’, ‘d’, and ‘e’. Let us further suppose that ‘f’ is the existence of living things. Here, we can analogically infer that, since the earth supports living things, quite possibly so does the other planet.

B. Dialectical Logic

1. The Dialectic of Hegel

Hegel’s Science of Logic has the reputation of being difficult to grasp. Unlike other logical systems, Hegel’s logic involves the world of God before the creation of the universe, describing the nature of God’s thinking during the Creation process.1

The essence of his logic can be found in the form Being-Nothing-Becoming (Sein-Nichts-Werden), and Being-Essence-Notion (Sein-Wesen-Begriff). The Notion (Begriff) finally becomes ldea (Idee) in its development. He explained this form as being the process of affirmation-negation-negation of the negation, or thesis-antithesis-synthesis. His theory is developed in the Doctrine of Being, theDoctrine of Essence, and the Doctrine of Notion, his three broad divisions of logic. It is difficult to understand the meaning of his Being-Nothing-Becoming (as presented in the Logic of Being). Hegel’s own explanation of it is vague, and scholars interpret it in different ways. Briefly stated, my best understanding of what he means is as follows:

Hegel regards God as Logos (Word), and he explains the world as having been formed from Logos in the same way as explained in St. John’s Gospel. He tries to clarify how the word has developed into the world. For him, the world is not the created thing, but things developed from Logos (Idea). What was Logos like before being developed? How did it develop to become all things? He answers these question through his ‘dialectic’. God Logos) first thinks of Being (Sein). The Being that exists in the beginning has no restrictions—i.e. no content or form; it is indeterminate and contentless (Bestimmungs-und-Inhaltslosigkeit). It is called pure Being (reines ein).

This Being, then, is actually Nothing, which means, not complete emptiness but something without a definite character or form. It has the possibility of assuming certain determinations; when it does, through the unity or synhesis of Being and Nothing, it will be a developed form of Being with content, the Becoming (Werden), which is neither Being nor Nothing, but Being that has passed through Nothing. This may be the true meaning of his saying that Being is denied by Nothing to become a new being, or Becoming, giving rise to another developing process (dialectical process).

The new starting point, also, is Being, but not in the same sense as Being in the process of Being-Nothing-Becoming; it is actually the very Becoming of that process. The new dialectical process is Being-Essence-Notion (Idea). Essence is the eternal, unchangeable aspect of Being, and Notion (Idea) is formed by the synthesis of Being and Essence. The Notion (Idea) here is not an abstract and static representation, like the concept in formal logic or in Kant’s logic, but a concrete and self-developing one.

This is Hegel’s Being-Nothing-Becoming and Being-Essence-Notion (Idea), a form that can be regarded as God’s thinking process before Creation. How do we know this? Simply by observing that man’s thinking develops in a similar way in recognizing something. Man’s thinking proceeds from the cognition of mere being to the cognition of essence and then to that of the idea. Initially, for example, man recognizes a flower only phenomenally, then he recognizes the essence of the flower, and then the idea of the flower is formed in our thinking, when the phenomenal attributes of the flower (color, shape, aroma, etc.) and the essence of a flower are united.

An idea is originally what is thought in mind, so it can't have the ability of thinking. But in systemizing his theory of Logic, Hegel seems to have dealt with God’s thinking only as the self-development of Idea. This point remains an aporia of his logic. Owing to this, philosophers find it difficult to understand the real meaning of his dialectic.

Many philosophers have tried to explain Being-Nothing-Becoming. One explanation is like this: imagine ice to be Being and heat to be Nothing (the negation, or antithesis of ice). When the ice is united with heat, it becomes water. Nothing (heat) is the motive, or mediator, for Being (ice) to develop into Becoming (water). According to another explanation, Being is like the day, Nothing is like the night, and Becoming is like the morning.

According to T. Takechi, Nothing is not ‘nothing of the being’, but not-Being. If reason is Being, matter will be Nothing, since matter is not reason (or spirit). This matter is not visible matter, but has the potential of taking visible form and shape. What reason has thought will be realized (as Becoming) by the interaction between reason (Being) and matter (not-Being). Scholars have set forth different explanations of Hegel’s views, first because he considered the Logos, or Idea, to be the same as God Himself; and also, because he failed to present an adequate explanation of his concept of Nothing. According to Hegel, the Idea formed in the world of God manifests itself as Nature in the ‘form of otherness’ (die Form des Anders-Sein); in other words, Nature is the opposite, the antithesis of Idea (thesis). So, if logic is considered to be the thesis, philosophy of Nature must be the antithesis. From Nature appears man—a spiritual being. The estranged Idea in Nature regains itself in man. Accordingly, the philosophy of Spirit cannot but be a synthesis in his dialectical system of philosophy. Finally, in the philosophy of Spirit, Idea develops to become the Absolute Spirit—in other words, it returns to ‘Being’ (God Himself), in a developed state. The process of development in Nature and in Spirit is also thesis-antithesis-synthesis, the dialectical process.

The natural world develops in three stages: the stage of Mechanics (Mechanik), the stage of Physics (Physik), and the stage of Organics (Organik). This, however, is not the development of the natural world itself, but the process of realizing the Idea (Idee). In other words, the natural world develops according to the development of the Idea. First, the Idea of force appeared; next, the Idea of physical phenomena originated; fina1ly, the Idea of living organisms came to appear. In correspondence with the development of Idea, nature itself develops; nature, therefore, is considered a Idea in the ‘form of otherness’.

Finally, man, a spiritual being, appeared. There are three kinds of spirit: subjective spirit (Subjektiver Geist), objective spirit (Objektiver Geist), and Absolute Spirit (Absoluter Geist). The subjective spirit is the spirit of an individual man. The objective spirit is the objectified spirit, or socialized spirit which goes beyond the scope of an individual; it develops through the stages of right (Recht), morality (Moralitat), and social ethics (Sittlichkeit).

Right is an elementary form of relationship among persons, where persons are considered as individuals, not as citizens of a state. By respecting other persons’ rights, one attains harmony with the universal will. Morality represents the duties that the universal will establishes as limitations to the individual will. The relation between right and morality is as that between subjective and objective; morality itself, however, is also quite subjective. Finally, social ethics appears for all men to obey. Thus, the objectified spirit undergoes the development of right, morality, and social ethics.

The first stage of social ethics is the family. If the members of a family are united in love, both love and liberty will be alive in that family. When the family increases to become a civil society, however, it will be confused, due to egoistic desires of man; both love and liberty will be restricted. The state, then, appears as the synthesis of the family and the civil society. This process of development is that of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis.

For Hegel, mankind’s hope lies in the establishment of a rational state, in which the Absolute Spirit (Logos, Idea) is fully realized. Men could live a vigorous life of love and liberty in such a state, since it would be controlled and ordered by the law of Reason. History is the process of the development of the Idea toward such a State.

What is the Absolute Spirit? Its first stage appears in man’s art; its second stage, in religion; and its third and highest stage, in philosophy. The Idea regains itself when it becomes philosophy. The purpose of the development of the Idea is to go back to the Absolute Spirit (in its developed form), passing through man, going through the stages of right, morality, social ethics (family, civil society, state), art, religion, and philosophy. When this is accomplished, the process of development is completed. Here we have touched upon a weak point in Hegel’s philosophy: there is no more development when the Idea becomes Absolute Spirit again. In a rough sketch, this is the dialectic of Hegel’s logic.

2. The Dialectic of Marx

Marx said Hegel’s dialectic stood on its head, and that his own stood on its feet. Hegel’s dialectic is idealistic; it says that natural things are not material, but are the Idea robed in the clothes of matter. Thus, natural things are nothing but a means of expressing the Idea externally.

Marx, however, maintains that matter—which has contradiction within itself—is the objective existence; the ‘Idea’ is nothing but a reflection of matter in man’s brain. The ‘Idea’ does not exist objectively; this notion is no more than a figment of Hegel’s imagination, Marx holds. Material development itself follows the process of thesis-antithesis-synthesis. Marx’s dialectic is, therefore, materialistic, while Hegel’s is idealistic. Along the lines of materialistic dialectic, a communistic system of logic has been developed by the followers of Marx. It is called ‘dialectical logic’, and one of its characteristics is its opposition to the principle of contradiction of formal logic. It says that the principle of contradiction is wrong, on the grounds that the change and development characteristic of all things imply that things contain negation in themselves. Accordingly, the proposition “A is not non-A” should be changed to “A is non-A (i.e., A is not A), as well as A is A.” (See Section 3 of this chapter.)

C. Symbolic Logic

Symbolic logic, or mathematical logic, is the study of methods of correct judgment through the use of mathematical symbols. It is a development of formal logic, but maintains that intuitive thinking, used in formal logic, lacks mathematical precision. The form and method of expression of a philosophical system—however great—must be carefully scrutinized in order for any existing faults to be disclosed. How can we disclose faults in expression? Symbolic logicians argue that correctness of expression can be examined by reducing everything to algebraic expression and then performing mathematical calculations on them. Symbolic logic, then, is actually symbolized formal logic.

As an example of the symbolization propositions are represented by p, q, r…. The negative of p is represented by ~p; ‘p and q’ is represented by ‘p•q’; ‘p or q’ is represented by ‘p ∨ q’; ‘if p, then q’ is represented by ‘p ⊃ q’. Any complex inference can be expressed by the simple use of these algebraic symbols.

D. Transcendental Logic

Transcendental logic refers chiefly to Kant’s logic. According to Kant-as introduced in “Epistemology” in this book-thinking necessarily takes on certain kinds of forms (category). These are thinking forms (Denkformen) or understanding forms (Verstand-formen). The thinking form itself is empty, unless it is filled with content (Inhalt), the sensible qualities of the object. Kant says, “thinking apart from contents is emptiness, and intuition without concepts is blindness.” In other words, man’s thinking is senseless apart from the cognition of the object. Accordingly, Kant’s transcendental logic is sometimes called “Epistemological logic.”

II. Unification Logic

A. Basic Standpoint

1. The Starting Point and Direction of Thought

The traditional logics as we have explained, mphasize the laws and forms of thinking. Unification logic, however, begins by considering the starting point of thinking and then discusses laws and forms.

Man’s existence is generally thought to be fortuitous. By the time we become aware of our own existence we are already living and do not know why. As Heidegger says, it seems a though we are meaninglessly thrown out into the world (Geworfenheit) by somebody unknown. Our thinking, also seems to be fortuitous and not necessary. Why do we think? This question is answered easily: we think in order to live. But what does it mean to live? This is related to the purpose of life. If man is a “creature,” he was created with a purpose. The Unification Principle asserts that man was created according to the Purpose of Creation and thus has purpose in life (as, for example a watch has the purpose of telling time). According to tbe Unification Principle, man is given two purposes: the purpose for the individual and the purpose for the whole. In the fulfillment of his dual purposes lies the meaning of his life.

It is for these two purposes that we think. Thinking should be conducted not for its own sake, but for the sake of practice, which has purpose and direction. Primarily, such thinking (original thinking) is based on the purpose for the whole and has the direction of realizing this purpose; secondarily, it is based on the purpose for the individual and has the direction of realizing this purpose. God has endowed us with the ability to think in order for us to accomplish these purposes and to follow these directions—in other words, in order for us to love one another, not to hurt or destroy one another or our environment. Man’s thinking was originally a kind of creative power, the power of practice. These are the lines along which logic should be established.

2. The Standard of Thinking

In Unification Thought, logic originates in the Original Image, as do Ontology and Epistemology. In order for any theory concerning the phenomenal world to be exact and true it must take into account the Original Image—i.e., the starting point of Creation. This is the basic standpoint of this thought.

It is generally thought that we are free to think about anything and to let our thoughts go as we please, since reason has freedom. Our thinking, however, should not deviate from the direction of the realization of the Purpose of Creation. Then, where does the standard for this direction come from? It comes from the logical structure of the Original Image.

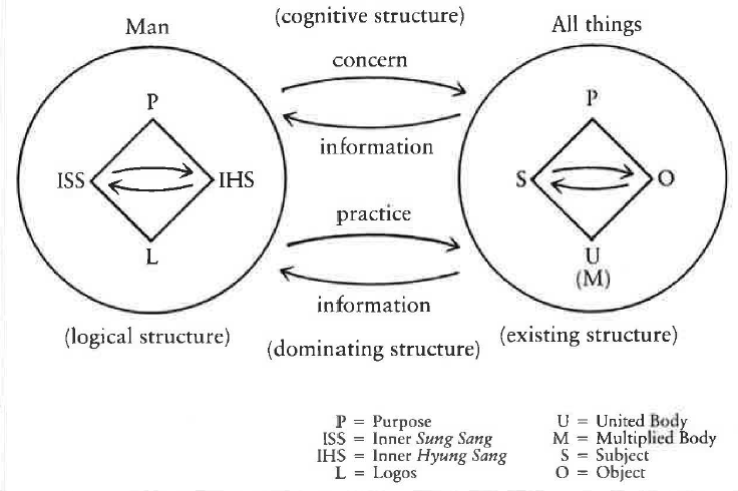

3. Interrelated Fields

Not only man’s logical structure, but also his cognitive structure, as well as the ontological structure of all beings, have their origins in the structure of the Original Image. Man’s practice on nature—that is, his domination of it, previously explained in the “Theory of the Original Image” as the process of forming the outer quadruple base—is also patterned after the structure of the Original Image. Thus, the logical structure, cognitive structure, existing structure, and the practicing structure (in all the practicing fields, such as education and industry), are naturally interrelated. This is fundamental to Unification Logic.

B. The Logical Structure of the Original Image

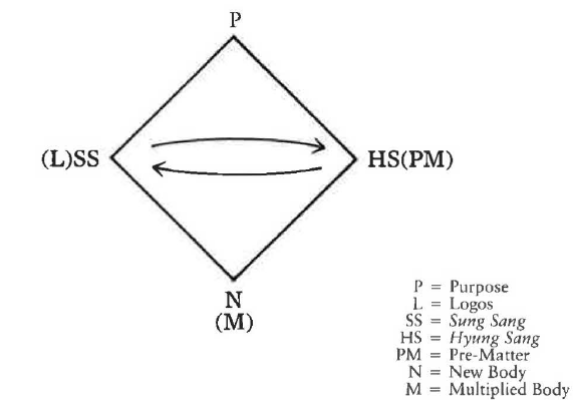

The structure of the Original Image that is most related to logic and thinking are the Inner Developing Quadruple Base. (Fig. 21)

The functions of the Inner Sung Sang are intellect, emotion, and will. Intellect is related to sensibility, understanding, and reason; emotion to feelings; and will to the desire to do something. These three functions are interconnected: there are emotion and will in intellect, intellect and will in emotion, and intellect and emotion in will. We think of them separately for the sake of convenience; in fact they are united. An intellectual action is one in which the intellectual aspect of the mind appears most strongly, even though the other functions ar involved as well. Modern psychology emphasizes the interconnectedness and inseparability of these three functions.

The Inner Hyung Sang contains ideas and concepts. Ideas are the concrete image of an individual being, such as a certain kind of fish, a dog, or a cow; concepts are images of common elements abstracted from ideas, such as ‘animal’ and ‘plant’. Concept, here, is not the same as Hegel’s notion (Begriff), but has the usual meaning of concept, such as the one used in the dispute about universals (Universalienstreit) in the Middle Ages. Besides ideas and concepts, the Inner Hyung Sang contains also original law and mathematical principle.

The Inner Sung Sang and Inner Hyung Sang engage in give-and-take action centering on Purpose. The result is Logos, or reason-law. Thus, a quadruple base is formed, called the Inner Developing Quadruple Base. The relative importance of reason and law (original law) vary, however, between the logos of man and the logos of animals and plants.

Purpose comes from Heart. Both the Inner Sung Sang and the Inner Hyung Sang begin to work in the direction of realizing the Purpose. This means that our thinking, also, is based on purpose; in other words, it has direction. The thinking of God is for realizing the Purpose of Creation, which is to realize joy through loving man and all creation, that is, through making them rejoice. Our thinking, also, should be for realizing the Purpose of Creation—in other words, it should be based on Heart, or love.

Because man is fallen, he does not think in this direction; rather, he has come to have evil ideas and evil concepts. As long as we live in a non-principled world, it is difficult for us to think in accordance with the Purpose of Creation, for give-and-take action with evil men easily brings about evil thinking. Sometime in the future, when the ideal world is free of evil persons, our thinking will naturally be in the direction of the Purpose of Creation, based on Heart, without any special teaching or effort. Many religious leaders have urged us not to think evil thoughts. They have not, however, clarified what the standard of thinking should be. In the Original Image, Logo is formed through the give-and-take action between Inner Sung Sang and Inner Hyung Sang centering on the Purpose of Creation established by Heart. This structure of Logos gives us the original standard of our thinking.

Logos engages in give-and-take action with the Hyung Sang (Original Hyung Sang), forming the Outer Developing Quadruple Base. This is the so-called two-staged structure of creation or in short, the two-staged structure. Logos, or the Inner Developing Quadruple Base, is closely related to the Outer Quadruple Base. Our thinking, therefore, should not stop at the inner quadruple base, but should develop outwards, forming the outer quadruple base. In other words, thinking is originally for practice.

C. Two Stages In the Process of Thinking and the Formation of Quadruple Bases

There are three stages of cognition: the perceptual stage, the understanding stage, and the rational stage. Since perceptual-stage cognition is regarded as a window through which the information coming in from outside is passively received it can be called direct cognition. In the understanding and rational rages, however, the process of thinking takes place. ln the understanding stage, thinking is influenced by sense-impressions from outside; not so in the rational stage. Thinking is an active participant in these last two stages, which form quadruple bases similar to those of the Original Image. (Fig. 22)

Kant’s epistemology, also, ascribes a three-stage process to cognition. In the perceptual stage, sense-impressions (content) are united with forms of intuition. In the understanding stage the content, which is already united with forms of intuition, is united also with thinking forms. ln the rational stage, thinking takes place freely, through the work of reason.

In Hegel, we find three stages of cognition as well. He considers the perceptual stage cognition as thesis, the understanding stage cognition as antithesis, and the rational stage cognition as synthesis. In the rational stage cognition, or thinking, proceeds first with negative reason and then with affirmative reason to reach the perfect cognition, or thinking.

In communism, the first stage is the perceptual stage, or the stage of sense-impressions, where the sensible qualities of an outside object are reflected in the brain. The second stage is the rational stage, where judgment and inference take place. The third stage is the practice stage, where rational knowledge is examined by practice.

In Unification Thought, both cognition and thinking are carried out through the establishment of quadruple bases. In terms of cerebral physiology, perceptual-stage cognition is carried out in the sensory areas of the cerebral cortex; understanding-stage cognition, in the parieto-temporo-preoccipital (PTP) association area; and rational-stage cognition, in the frontal association area. (See chapter 4, “Epistemology.”)

The PTP association area has countless nerve cells. Each nerve cell is connected, directly or indirectly, to fourteen billion other cells in the cerebral cortex, Just as a telephone is connected virtually to millions of other telephones throughout the world. Just as we can talk with anyone in the world by telephone, any kind of information (prototypes) can be freely shared, through give-and-take action, among the nerve cells. In this way, quadruple bases for thinking and for cognition can be easily formed.

In the understanding stage, thinking is restrained by its involvement with sense-impressions (content) from the outer world. In this stage, the content from the outside and the prototype from the inside are collated to complete a cognition; in other words, a completing quadruple base is formed as a cognitive structure. In the rational stage, however, thinking is performed freely, using information obtained from the understanding stage, but not restrained by anything from the outside. Accordingly thinking is developed in this stage. Development of thinking refers to successive fragmentary instances of thinking. Saying that thinking develops is the same as saying that new instances of thinking appear one after another. In this case, each instance of thinking forms its own completing quadruple base. The completing quadruple base, although it is developing while it is formed, is identity-maintaining after it has been forrned, that is after a thought is completed. In th erational stage therefore, the process of thinking is developing and at the same time it has the identity-maintaining aspect.

Let us depict this figuratively. A guest comes to the reception room of a mansion and requests to speak with the owner. A servant announces him to the owner and is told to show the guest to the drawing room. The guest and the host meet in the drawing room and talk, but the host cannot think at random, because his thinking is restrained by the talking of his guest. When the conversation ends, the host retires to his private chamber, where he thinks, reads, paints, sleeps and doe as he likes. The reception room correspond to the sensory centers of the brain; the drawing room, to the PTP association area, where understanding-stage thinking is carried out; and the private chamber, to the frontal lobe, where unrestrained, rational-stage thinking takes place.

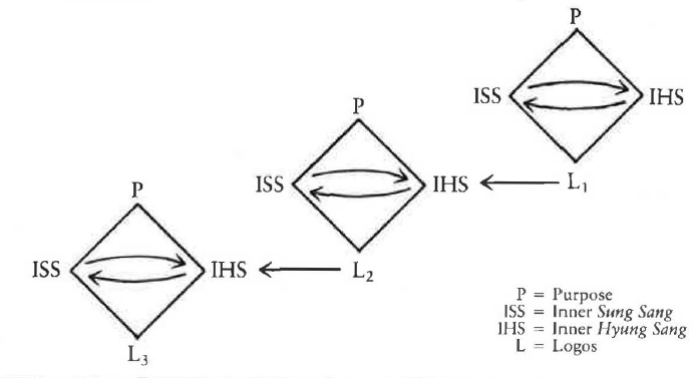

In rational-stage thinking, the logos (plan) is formed by the give-and-take action between the Inner Sung Sang and Inner Hyung Sang. The thinking process may be terminated with the attainment of a conclusion (logos), which is called a first-stage conclusion. Sometimes this conclusion is used, along with other ideas, to make up the Inner Hyung Sang of a second-stage quadruple base, giving rise to a second-stage conclusion (logos 2). The thinking process may be completed here, or may be indefinitely extended over numerous other stages, in spiral development, figuratively speaking. (Fig. 23)

D. The Basic Forms of Thinking

An understanding-stage cognition, or thinking, is realized by the give-and-take action between sense-impressions and prototypes—i.e., by the formation of a reciprocal relationship between them, centering on purpose. A prototype consists of protoimages and images of form in the protoconsciousness (the consciousness on the cellular level). A protoimage is the image of a single cell, or of many cells; an image of form is that of the existing form of a single cell, or that of relationship between cells—such as Subject and Object, Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, and Position and Settlement. The images of form become the thinking forms in cognition and in thinking.

Since the lower nerve center knows the normal stage of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang of the cecum, for example, in the case of appendicitis it immediately knows the change through the information from the appendix and takes appropriate measures to relieve the inflammation. (It is similar to a watchmaker being able to repair a broken watch because he knows its normal state.)

The Positivity and Negativity of bodily functions are seen in such systems as the Autonomic Nervous System, whose sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves are often antagonistic in function—i.e., one is accelerating and the other is restraining. When the function of the stomach muscles, for instance, is over-strengthened, gastric cramp may appear; when it is too weak for a long time, gastroptosis may occur. The lower nerve center, knowing all the information concerning the activities of the stomach muscles, regulates their functioning. If the regulation is disturbed, disorders, such as cramps and ptosis, come to appear. It can do this because it has the sense of positivity and negativity. Cells of the lower central nervous system have information on the arteries and veins, which exist in a subject-object relationship. Of course, the cells do not know the concepts of Sung Sang and Hyung Sang, subject and object, etc., but they have an awareness of these correlative relationships. Thus, when the relationship is disturbed, the lower central nerve cells try to respond to the disturbance promptly.

Cells know neither the concept of time nor of space, but they have a sense of time (that something is lasting) and a sense of space (position and direction). White corpuscles, for instance, move accurately to an inflamed part of the body; the semicircular canals of the ear, knowing direction, enable us to maintain our balance through the central nervous system.

‘Infinity’ and ‘finiteness’ are philosophical concepts, but each nerve cell has the sense of infinity and finiteness. Infinity in living things means the durability of the actions of cells, tissues, organs, etc. Finiteness refers to the limitation of the span of life. Nerve cells have the awareness of such durability and limitation.

Perceived Images, which consist of protoimages and images of form, are considered to be stored in the spinal cord, hindbrain and the limbic system to become prototypes. The lower central nerves maintain normal bodily conditions by using this information in a feedback system, a process which our consciousness (cerebral cortex) is unaware of. Perceived images, also, influence our conscious thinking. Figuratively speaking, thinking can be compared to a soccer game: even though the players seem to be running and kicking at random, in fact their motions and actions are, regulated by soccer rules. Similarly, our thinking is influenced by the perceived images. We cannot think about outside sensations in the cerebral cortex independently of the protoimage and image of form, which come from the lower nerve center. That our thinking is regulated by the image of form is the same a saying that we have thinking forms.

Unification Thought idenyifies ten basic thinking forms (though there may be more), which are established from the concepts of give-and-take action and the quadruple bases. Many forms and concepts of the category established by other philosophers correspond to the thinking forms in Unification Thought. “Essence and phenomenon,” for example, correspond to “Sung Sang and Hyung Sang.” I have divided the Unification Thought thinking forms into two groups, the first consisting of the ten basic forms (first category), and the second consisting of those forms derived from the first (second category). The first category is already shown in chapter 4, “Epistemology.” The second category, which is not limited in number and contains the traditionally used concepts, is as follows.

- quality and quantity

- content and form

- essence and phenomenon

- cause and effect

- totality and individuality

- abstract and concrete

- substance and attribute

Someone may wonder why we have used such concepts as ‘Sung Sang and Hyung Sang’ instead of ‘essence and phenomena’ and ‘content and form’, or why we have used such purely new concepts as ‘existence and force’, ‘relation and affinity’, and so on as concepts in our category (first category).

Without Quadruple Base, C-B-H action, and give-and-take action, we would no longer have the Unification Principle. Since these are fundamental concepts, our category must be based upon them. As a new system of thought, Unification Thought naturally gives rise to new concepts. A category can be looked upon as a sign-board for the system of thought; it is natural, therefore, for the Unification Thought category to be new as well.

Marx’s philosophy has a category that is characteristic of Marx; Kant’s and Hegel’s philosophies do so also. Similarly, the first category of Unification Thought, which comprises ten thinking forms, is uniquely characteristic of Unification Thought.

E. The Basic Law of Thinking

Formal logic has given us two fundamental principles (the principles of identity and contradiction) and two more, derived from them (the principles of excluded middle and sufficient reason). In Unification Thought the most fundamental principle is the principle, or law, of give-and-take action, or in short, the give-and-take law, or coaction law.2

I began this section by explaining that the Quadruple Bases in the Original Image are the origin and standard of our thinking. These Quadruple Bases are established by give-and-take action; accordingly, the basic law of thinking, upon which the principle of identity and the principle of contradiction and all other laws stand, is the give-and-take law. (See item G. below.)

In formal logic, logical terms, such as “be,” “be not,” “and,” “or,” and “if…then…” —play as important a role as that of bone structure in the body, because without them, a proposition cannot be established and inferences cannot be made. In Unification Thought, a proposition or an inference containing such logical terms is dealt with as an instance of collation-type (contrast-type) give-and-take action, for logical terms are viewed as means of establishing relationships between concepts or between propositions.

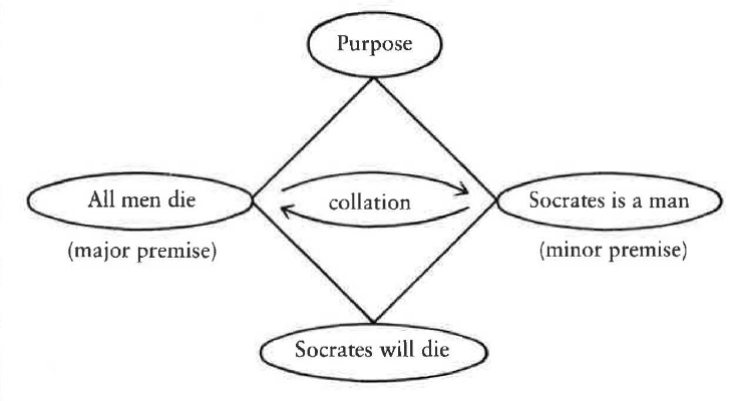

The laws of thinking, which are expressed through the use of logical terms, are all based on the give-and-take law. A representative deductive inference, syllogism, which is expressed in the form “if [A (major premise) and B (minor premise)], then C (conclusion),” is subject to the give-and-take law.

Let me explain this in the following example.

- All men die

- Socrates is a man

- Therefore, Socrates will die

In this example, we want to know what will become of Socrates in the future; this is the purpose in our thinking. Next, the two propositions (“all men die” and “Socrates is a man”) are compared, or collated. The first proposition, the major premise, is the subjective proposition; the second one, the minor premise, is the objective proposition. By collating them through the correlative give-and-take law, we find that the range of the major premise is broader than, and includes that of, the minor premise; in other words, Socrates belongs to “man’, and therefore, will die. (Fig. 24)

Even a single proposition, such as “Man is mortal”, is based on the give-and-take law. The subject “man” and the predicative adjective “mortal” are connected by the logical term “is”. One concludes that “man is mortal” by comparing “man” and “mortal”, according to the give-and-take law.

We can conclude that “Some Koreans are honest,” if the proposition “All Koreans are honest” is true. This is immediate inference, in which the conclusion can be directly derived from a single premise. Immediate inference is actually an abbreviated kind of syllogism (mediate inference). In the example above, the minor premise “some people are Korean” is omitted. Thus, even immediate inference is based on the give-and-take law. In fact, so is the premise “All Koreans are honest,” which is the result of comparing ‘All Koreans’ and ‘honest’ through the give-and-take law. We can similarly show that inductive inferences, also, are based on the give-and-take law.

By the way, if our thinking is subject to laws, do we have any freedom of thought? Yes we do. As stated before, Logos is formed by the give-and-take action of the Inner Sung Sang and Inner Hyung Sang. The element of reason in the Inner Sung Sang has freedom, whereas the element of law in the Inner Hyung Sang is predetermined. What kind of freedom, then, does reason have? There are numerous concepts and ideas in the Inner Hyung Sang; reason can freely select any of them in order to form a Logos, even though the purpose has been decided beforehand.

Man has countless concepts and ideas, acquired from life-experiences, and he can select any of them in thinking or making a plan. He can exercise his freedom without violating the law. In other words, he can freely perform give-and-take action in thinking.

III. A Critique of Traditional Logic

A. Formal Logic

Though we approve its basic laws, still we find something lacking in the foundation of formal logic. All beings carry out give-and-take action within themselves in order to exist. Between man and the rest of creation, there are two kinds of give-and-take action. First, man takes an interest in all things (concern), and they return information (cognition) to him; second, man works on all things (practice) and they return information (cognition) to him. The former give-and-take action forms the cognitive structure (cognitive quadruple base); the latter, the dominating structure (dominating quadruple base). In addition, there is give-and-take action in the mind of man, forming the logical structure (logical quadruple base), and in each creation, forming the existing structure (existing quadruple base), both among men and among created beings. These structures are closely connected to one another.

This means that man’s logical structure is not independent or isolated; rather, it is related to other structures. One cannot think normally apart from the cognitive and dominating structures. In other words, man’s thinking is performed in cognizing as well as in practicing. (Fig. 25) The formal logic itself has only dealt with the logical structure without paying attention to other structures.

Of course further study about judgment forms and inference forms is necessary, but these matters should be entrusted to logicians.

B. Symbolic Logic

Precision in thinking and expressing thoughts is a goal worth striving for, so we accept symoblic logic as such. The full range of human communication, however, encompasses more than mere mathematical accuracy in the use of language, as shown below.

Logos is formed through the give-and-take action between the Inner Sung Sang and Inner Hyung Sang. Since the Inner Hyung Sang contains original laws and mathematical principles, all created beings (created through the Logos) have these laws and principles. Scientists have conducted research on these principles and have been able to send men to the moon as a result of their discoveries. Man, also, has mathematical principles, not only in his physical body, but also in his language. By making use of these principles, even if unconsciously, he thinks and speaks accurately and correctly. These principles come from the Inner Hyung Sang of God, and reason comes from the Inner Sung Sang of God. But the motive (center) of the give-and-take action between them is the Heart behind Purpose. Heart, therefore, is in the highest position. This means that man is not only a being of logos (reason, law), but also a being of pathos, (heart, love, emotion). By stressing only mathematical accuracy, the emotional factor cannot be conveyed. Thinking itself is for practice, which requires give-and-take action (cooperation) with others, and this can only take place if thoughts are communicated to others. But, if the thinking language is totally transformed into mathematical symbols, the emotional content of thinking will disappear and the flow of communication will be impaired.

For instance, if someone shouts, “Fire!” we do not know from the word itself whether he means, “This is a fire,” or “There is a fire burning now,” or something else. We can understand the meaning, however, because there is an emotional factor in his expression. Here, the question of grammatical accuracy (essential in symbolic logic) is actually unimportant, for “Fire!” is an emotional utterance, not a rational one. We use emotional utterances especially in cases of emergency, and they are understood immediately (intuitively).

Since man is the union of logos and pathos, our language has both an intellectual and an emotional aspect. If we root out all emotional utterances, we are rooting out a part of our humanness. In fact, people whose language is often inaccurate may actually be more warm-hearted than those whose language is always precise.

Kant’s language and behavior, for instance, were reputed to be consistent and accurate. People could set their watches by him, for he always passed by the same place at the same time every day. Similarly, there is a rigor to his philosophy, and we feel constrained by it. We need not be so pedantic. Jesus’ words in the Bible were sometimes not logical, yet we consider them to be true, because they were accompanied by God’s love. We cannot but say that symbolic logic is one-sided, because it disregards the factor of pathos in normal language.

C. Hegel’s Logic

Hegel considered Logos to be God, making the created (Logos) the Creator (God). In Unification Thought, Logos is the Multiplied (New) Body formed through the give-and-take action between Inner Sung Sang and Inner Hyung Sang, centering on Purpose. By making Logos the starting point of his logic, he lost the purposive element in his philosophy; consequently, he was drawn to making serious errors.

The Unification Principle explains that development is realized through the give-and-take action between correlative elements. Nothing is produced by a single element. But Hegel had no correlative element in Reason (Logos), which is considered to be thesis, so he had to give it an antithesis. Consequently, the dialectical process of thesis-antithesis-synthesis became purposeless and purely mechanical.

The thesis (Being) is supposed to proceed to the antithesis (Nothing), but since this antithesis is nothing, it does not substantially exist. In this way, the thesis, denied by the antithesis, cannot but turn into thesis again. This is the synthesis. The synthesis, therefore, necessarily returns to a stage similar to what it was before. Thus, Hegel’s logic is actually a returning, or completing, system; in his philosophy development cannot continue eternally, but is destined to end sooner or later. This point was criticized by Marx and Engels.

According to Unification Thought, development is realized by the harmonious give-and-take action between subject and object, centering on purpose. In Hegel’s philosophy, however, the thesis and antithesis oppose each other. This assertion gave rise to the philosophy of struggle. Hegel’s philosophy lacks any theoretical basis for love. By making Reason (Logos) equal to God, he excluded the aspect of God’s love.

Hegel said nature is the estranged Idea (God). If so, we have a kind of pantheism, in which we can see Logos (God) in nature. This could be understood also as the assertion “nature is God, therefore God is no more than nature.” Such an assertion can lead to materialism; in fact, some have said that Hegel’s pantheistic tendency was largely responsible for Marx’s materialism.

According to Hegel, the appearance of nature is a stepping stone for the appearance of man. Idea manifesting itself first as nature and then as man, finally returns to Idea (after realizing itself completely), or the Absolute Spirit. Nature becomes irrelevant after man appears. It can be compared to scaffolding, which is needed while a building (man) is being made, but becomes unnecessary after its completion. In Hegel, nature need not be useful to man’s life. In Unification Thought, however, nature is man’s object, both for his joy and for his dominion.

In Hegel’s view, the history of mankind is an account of man’s puppet-like manipulation by Reason. This is called the trick of reason (List der Vernunft). If this is true, what becomes of man’s contribution to history? What should man live for, and why should he work hard, if he is only being used? There is no need or incentive for making effort; since there is no room for man’s own portion of responsibility. In the Unification Thought view, the progress of human history has been greatly affected by man’s success or failure in the accomplishment of his portion of responsibility. (See chapter 10, “Theory of History.”)

Yet Hegel was ready to go to war to defend Prussia, his rational state. (Apparently the Absolute Spirit does not refrain from going to war.) Why should we believe in God anyway? Such problem in Hegel’s view of history have arisen from his making Logos equal to God and his considering the progress of history the self-realization of Logos (Idea).

There is one more thing to be pointed out. Hegel’s philosophy may look like a philosophy of development; actually, it is not. Hegel believed that Prussia was to be the rational state appearing at the consummation of history. History need not develop any longer. His philosophy, therefore, was destined to die with the disappearance of Prussia.

The position of Logos in Hegel’s philosophy corresponds to that of the Original Image in Unification Thought. His dialectic within the Logos corresponds to the give-and-take action within the Original Image. Hegel’s thesis-antithesis-synthesis corresponds to Chung-Boon-Hap. Hegel’s ‘antithesis’ corresponds to Hyung Sang (pre-matter). What Hegel intended to accomplish through the ‘completing dialectic’ is accomplished by the dynamic give-and-take action and static give-and-take action of Unification Thought. What Hegel understands by ‘nature’ corresponds, though symbolically, to the understanding of the Original Image through ‘all things’ in Unification Thought. Finally, Hegel’s pantheistic tendency is surpassed by the Pan-Divine-Image Theory of Unification Thought.

D. Materialistic Dialectic

The idealistic dialectic, as demonstrated above, has many problems bur the materiali tic dialectic even more. The first problem concerns the starting point of materialistic dialectic, and the second one concern its view on the principle of contradiction of formal logic.First, about the starting point of materialistic dialectic. Hegel starts with the Logos, but Marx has no starting point, unless matter is considered that. Marx used Hegel’s dialectic after taking away the starting point—i.e., Logos.

If matter is the starting point, then natural laws must be considered as attributes of matter. Even admitting this, we cannot say that law are matter itself. Matter is supposed to have no definite laws originally, since it consists of atoms, or more precisely, of elementary particles, which are supposed to have originated from energy without any kind of restriction or law. But matter consists of atoms, which have a certain structure, with atomic weight, atomic numbers, atomic shell, atomic value, etc. We know that there are many kinds of atoms, each of which has a different structure and character. The atomic structure (thus, the atomic character) has an influence upon chemical and physical laws (i.e., natural laws). How can atoms come to have such different structures and laws? In other words, how did matter come to have such attributes as laws, character, etc.? This question cannot be solved by materialism. Therefore, the materialistic dialectic, as a law of development, clearly lacks a definite starting point for its theory of dialectic development.

Second, I would like to criticize the view of the materialistic dialectic on the principle of contradiction of formal logic. The principle of identity says that “A is A,” and the principle of contradiction says that “A is not non-A.” These two principles have the same meaning, only differing in expression. But the communist dialectic says that “A is A and at the same time is non-A.” Communists say that development is not possible if A is only A, but is possible if A is not only A, but simultaneously is non-A.

They say that a hen’s egg must be a non-egg as well as an egg in order for it to develop into a chicken. The non-egg, or negation of the egg, is supposed to be the embryo. The antinomic conclusion, “an egg is a non-egg as well as an egg”, is against the principle of contradiction. Credit for its formulation should go to Hegel, who said that a notion cannot develop unless it has a negative element (negation of the notion) within itself.

What does the proposition, “An egg is a non-egg as well as an egg” mean? In this case, non-egg means the negation of the egg—that is, the embryo. Accordingly, this proposition can be changed to “An egg is an embryo as well as an egg.” We know that an egg consists of four elements: the white, the yolk, the shell, and the embryo. So, to say that an egg is a non-egg (embryo) is the same as saying that the four elements equal one element, or the total equals one of its parts. This proposition is quite false; it is not a logical statement.

In the Unification Thought view, development takes place without contradicting either the principle of identity or the principle of contradiction. I explained before that the logical structure originates from the dynamic structure of the Original Image, or the Developing Quadruple Bases; still we should remember that the Developing Quadruple Bases cannot be separated from the Identity-Maintaining Quadruple Bases. Accordingly, thinking, besides being dynamic, has also an identity-maintaining aspect.

The result of the copulation (give-and-take action centering on the purpose of producing progeny) of a cock and a hen is a fertilized egg. This is the first-stage dynamic quadruple base. In this process the principles of laying eggs and of mating male and female remain unchanged. This is the identity-maintaining aspect.

The two main constituents of an egg are the embryo and the other contents (the yolk and the white). When these two elements enter into dynamic give-and-take action centering on purpose, the egg becomes a chicken. This is the second-stage dynamic quadruple base. In the first-stage dynamic quadruple base, through which an egg is laid, the egg is simply an egg; in the second stage, however, it becomes a chicken. The developing (dynamic) quadruple bases, then, have an identity-maintaining aspect. When an egg is laid, it is an egg only, and not simultaneously an egg and a non-egg; when it becomes a chicken, in the second stage, it is a chicken only, and not simultaneously a chicken and a non-chicken. A chicken is not born by the struggle between egg and non-egg, but it is born purely from an egg through the give-and-take action between correlative elements within it.

Understanding-stage thinking (or cognition) is predominantly identity-maintaining, since it becomes complete, to a certain extent, with the collation of the inner prototype and the outer sense-impressions. Rational-stage thinking, however, is predominantly developing, since rational thinking is a continuously and infinitely developing process. Yet it has also a completing (i.e., identity-maintaining) aspect, because rational thinking is carried out step by step, and at each step, thinking is completed to some extent. Unification Thought, then, recognizes both the principle of identity and the principle of contradiction, as it recognizes the identity-maintaining aspect of every being.

In 1950, Stalin published his book Marxism and Problems of Linguistics, where he stated that formal logic should be accepted even in communist society. Before that, there was a heated discussion among scholars in U.S.S.R. concerning formal logic. Some scholars maintained that the forms and laws of formal logic should be abandoned, since they belong to the superstructure and have class characteristics; others maintained that they should be accepted, since any proposition would become invalid if the principle of identity and the principle of contradiction were denied. Then, Stalin concluded that formal logic does not belong to the superstructure and has no class characteristics and, therefore, should be accepted.

Aside from the question whether logic belongs to the superstructure or not, this fact shows that the materialistic dialectic could not but approve of the unchanging aspect in the process of development (of thinking), without being able to carry out the dialectical principle that states that everything is not in the state of immutability, but constantly changes and develops. This implies a modification, or strictly speaking a collapse, of the materialistic dialectic. To put it another way, this fact shows that Unification Thought—which stresses the unity of identity-maintenance and development and the unity of unchangeability and changeability in all things—is right.

In conclusion, I would like to present a diagrammatic comparison of Unification Logic, formal logic, materialistic dialectical logic, and transcendental logic. (Fig. 26)

| UNIFICATION LOGIC | FORMAL LOGIC | MATERIALISTIC DIALECTICAL LOGIC | TRANSCENDENTAL LOGIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| thinking form | objective & subjective | subjective | objective | subjective |

| content of thinking | objective & subjective | objective | objective | |

| law of thinking | give-and-take law | principle of identity, principle of contradiction | dialectic | transcendental method |

| basis of thinking | structure of the Original Image (logical structure) | |||

| characteristics | collation | formalism | reflection | synthesis |

Notes

1 In his “Science of Logic,” Hegel says, “This content shows forth God as He is in His eternal essence before the creation of nature and of a finite spirit.” (The Philosophy of Hegel, edited by Carl J. Friedrich, New York: The Modern Library, 1953, p. 186).

2 When we fight with words against the dialectic based on communist philosophy, the terms with which we fight need to be concise and sharply anti-dialectical. The term ‘give-and-take action’ is the best weapon to overcome the term ‘dialectic’, but its expression does not seem to be concise enough. So, I have created the new terms ‘coaction’ (noun) and ‘coactic’ (adjective) with the same meaning as ‘give-and-take action’, and I would like to use the new terms in combination with ‘give-and-take action’, especially in criticizing communistic philosophy. Accordingly, the law of give-and-take action can be expressed as ‘coaction law’; similarly, the term ‘give-and-take unitism’ can be expressed as coactic unitism’.