![]()

The Words of the Moody Family

|

|

The Words of the Moody Family |

Glenda

Moody

In the summer of 1967, Glenda Moody encountered a couple of black teenagers running wind sprint down a back street in a Washington DC ghetto. Hungry and impoverished, they were dodging the police with a bag of stolen groceries! Glenda immediately noticed the tremendous speed and potential of one of the youths. When she spotted him again at a track meet a few weeks later, she mentioned that his sprinting mechanics could use some improvement.

Well, if she thought she knew so much, he retorted, why didn't she help him train? His words flipped the switch in Glenda's mind -- the light went on, and she was inspired to start a track club of her own. She was a college senior, herself a track and field athlete, and had been a member of the Unification Church for two years.

At that time the DC high schools had no real training or organized competition in track and field, so over the summer Glenda structured a suitable program for both under the auspices of the DC Department of Recreation. She coached discus and shot-put herself. By the end of the summer she had a small nucleus of eight young men, and on that foundation she incorporated the DC Striders. The DC Striders Track Club sponsored track meets and enabled her athletes to compete and gain exposure in other main events around the country. The young man she had seen fleeing from the law became her very first frontline runner!

Throughout the fall and winter, as Glenda trained and observed her athletes, her awareness of their athletic potential, intelligence, and stamina intensified. What they desperately needed was confidence and self-respect. Glenda pushed them with unwavering love and unrelenting discipline, and they responded. Not only did their running time and performance improve, but so did their grades at school; the more they applied themselves to their sport, the more they also applied themselves to their studies. They realized that if they achieved a high standard, they could qualify for college scholarships.

By watching these developments Glenda conceived of her Scholarship Acquisition Program. At first she began to talk to college coaches and admissions officers by phone, giving them information about her athletes and encouraging them to consider them for scholarships. Then she began to send hand-written profiles to about 50 to 75 colleges at a time; finally she developed professional, typewritten information packets and sent them out to 1300 colleges annually. The motto of the DC Striders became "Springing from Athletic Success into Academic Stardom!'

Glenda wanted to use track and field as a vehicle to raise black youth over the barriers of despair that bound them so pitilessly to ghetto life. She was determined to open a new frontier that could work as an "equalizer" and offer opportunities to these youth who, in facing insurmountable hardships, had been sorely conditioned to underachieve. Through the club they could establish supportive peer relationships, and through their athletic accomplishment they could learn the importance of discipline in reaching life goals and restore their sense of personhood and pride. DC Striders was another chance -- a new starting line -- for many.

Glenda trained students at local universities, such as American University and Catholic University, but she also worked at high schools that were deep within the urban ghettos. The late 1960s was a time of great racial tension, and rioting often broke out there. It was not an auspicious time for a young white woman to attempt to penetrate and restore any aspect of black ghetto life. Colleagues and other observers in the surrounding community severely ridiculed and persecuted her in the beginning, not only because she was a white person working among blacks, but because she was a woman working in a male profession. It came as a great surprise to them when her Track Club began to excel nonetheless. Also, her Scholarship Acquisition Program directly challenged deeply ingrained racial prejudices within the educational system. Gradually, however, her efforts and the accomplishments of her athletes were able to stretch open the doors of even the finest Ivy League colleges. In the end, over 3,000 of the athletes Glenda trained won athletic and academic scholarships, and over 90 percent graduated. The Striders program challenged barriers of race, gender, and class all at the same time.

In fact, none of the coaches, businessmen, school administrators, city politicians, or journalists who watched her program grow knew exactly what made Glenda tick. People noticed that her runners were mysteriously transformed: Here was a team of black men who didn't fight or swear, but rather acted like a close-knit family. Besides showing respect and support for each other, they even seemed to have fun under the pressure of competition!

Those of Glenda's athletes who had already gained admission to college would return over the summer to train with her high school athletes. They inspired the younger ones to work even harder, and provided such stiff competition that they advanced dramatically. When Striders high school athletes began to beat college athletes in meets around the country, other coaches really became desperate to know the secret of Glenda's coaching ability. Of course, it was cooperation and love -- the practice of God's heart and the Principle which the Striders was proving true.

Glenda confided, "I learned that if I was going to discipline each runner as hard as I wanted to, and come down on him as hard as I needed to in order to change his life, I had to go to the other extreme and love him unconditionally and passionately. When the kids saw that I loved them more than they could love themselves, and that I believe in their future more than they did themselves, then their lives really did change"

For example, one youth came from such a poor and deprived family that he rarely had anything to eat. Glenda usually fed him at the local church center. He had very little confidence and was a poor runner. Yet one summer he broke through and became such an excellent quarter-miler that he received a full scholarship to Catholic University. He was an All- American* in track and field all four years and graduated with a degree in art. Besides becoming a very fine artist, he worked as head coach for the DC Striders for many years. (After 1975 Glenda gave up coaching and assumed a purely administrative position.)

Another youth came from a family with an entrenched welfare mentality; his parents didn't care about him at all. After much struggle he also became an excellent quarter-miler and an outstanding football player at Howard University. At one time he was considered the best quarter-miler in America. Now a very sincere and articulate person, he is also a high school teacher.

Glenda taught her runners the principles of unity and give-and-take action. In a relay race for example, if any one of the runners dropped the baton, Glenda would not permit them to accuse each other; she told them that they were all responsible. She instructed them to study, learn about, and come to "feel" each other -- not only the way they picked up the baton, but each other's whole style, personality, and spirit. Passing the baton was a matter of "passing energy," and to gain the power to perform without any possibility of error, they had to become completely one.

The athletic and college community began to take the Striders seriously when Strider Maurice Peoples made the U.S. Olympic Team in 1972 and competed in the mile relay event. The following year he broke the world record for the open quarter in the mile relay at the NCAA college division meets. For the next three years the Striders had one of the finest mile relay teams in the world, with its runners holding the fastest time in the nation each year.

In 1970, with the inauguration of the Title IX program which enforced equal athletic opportunities for women, Glenda was able to start coaching women as well as men. Before that time, colleges would not give athletic scholarships to women. One of her first female runners, Benita Fitzgerald- Brown, won a gold medal in the high hurdle event at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. Just last July, she won her heat in the same event at the Goodwill Games in Moscow.

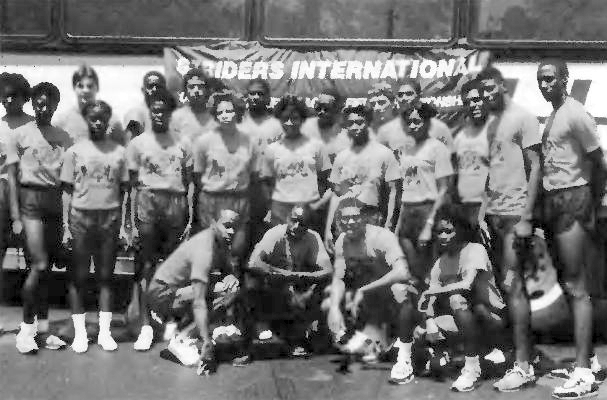

The Striders was one of the first social programs that grew out of the Unification movement. As a nonprofit organization, it has received funding from the church as well as grants from a number of well-known foundations and banks. In 1983 administrative tangles forced Glenda to incorporate anew as "Striders International." The change did not stop the flow of success, but liberated new vision and energy instead. One year and half ago, Glenda felt called to set up a clinic through which she could consolidate the Striders program here in America and bring it to others around the world. One June 13-15 of this year, that clinic became a reality.

* An elite, in which membership is determined by qualifying votes from college athletic directors and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) officials.