![]()

The Words of the Moffitt Family

|

|

The Words of the Moffitt Family |

The World Media Association (WMA) held its fourth Opinion Leader's Tour of the Soviet Union from October 24 to November 6, 1987. The participants on the tour -- international editors, columnists, reporters, and members of public policy institutes from eight countries -- visited the Soviet cities of Moscow, Leningrad, and Samarkand (a city in Central Asia just north of Afghanistan). Three previous WMA fact-finding tours to the Soviet Union were conducted in 1982, 1983, and 1986. In the following excerpts from his interview with Victoria Clevenger, WMA Executive Director Larry Moffitt gives us a look at what he experienced there.

Question: Having visited the Soviet Union four times now, do you have one dominant impression from your experiences?

What impresses me most is the plight of the people. If you go to the Soviet Union with a heart of restoration, you will hate the government, and as some on our tours have done, even get physically ill from the spiritual oppression you feel every second you are there. But you will absolutely fall in love with the people. You will cherish them and want to help them -- give them things, meet their families, become part of them.

Russians are legendary for their love of children and the way they dote on them with toys. I was on a streetcar one day, and a child got her glove caught in the door after she and her parents got off. When the vehicle began moving again, it dragged her for about a foot or so before her glove came off. She screamed, and the parents shouted for the streetcar to stop, which it did instantly. In his rearview mirror the driver noted she was okay and started off again, but the other passengers suddenly began pounding on the partition behind the driver and shouting for him to stop. The driver stopped and every person on the bus scrambled out to fuss over the little girl and make sure she was all right. A moving tableau and quite illustrative of the Russian character.

Seeing things like this -- and remembering how Heung Jin Nim told us that if Lenin had responded to God, then Russia, with such a strong Christian foundation, would be like heaven today -- I am all the more amazed that communism could establish its first national foundation in that country. I think there must be many spiritual reasons behind it, failures unconnected with Russia itself.

It shows that even under a system that consciously works to snuff out the spiritual life from society and create suspicions that alienate everyone from everyone else, a live ember still smolders under the layers of brutality, nastiness, and poverty the Soviet government has cynically heaped upon its citizens for seven decades.

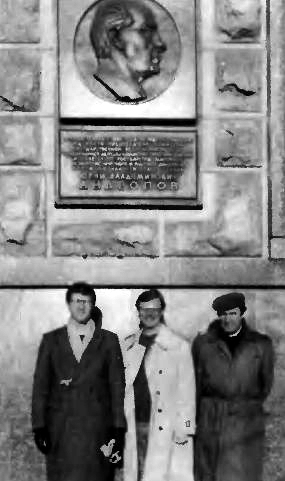

Before

being chased away, Bill Lay, Larry Moffitt, and Tom Ward have their

picture snapped at the Moscow KGB headquarters and prison. Behind

them is a plaque dedicated to Andropov, once head of the KGB.

Question: What is the purpose of your fact-finding tours?

These tours are designed to give journalists a first-hand experience of life in the Soviet Union and an opportunity to meet representatives of the official Soviet news services. Through CAUSA and other organizations, we are made aware of journalists who really know what's going on in the Soviet Union and want to see it with their own eyes. These are the kind of people we invite.

Question: How many people were on this tour, and what were they like?

We had 60 this time, the largest of the four tours. They were also the most righteous and knowledgeable group so far, with some of the most preeminent Sovietologists in the world on the tour. Among them were John Dunlop, associate director of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University; Arnold Beichman, a Hoover Institution historian who writes for The Washington Times; and Tom Ward and Bill Lay from CAUSA. All were indignant at the crushing of the Soviet people and the destruction of the human spirit by the government.

Question: Were there signs the KGB took particular notice of your group?

One of our participants, an eminent scholar on the Ukraine, was followed and harassed in a kind of childish way. He speaks Russian and was denied visas to visit the USSR many times previously, until he came with our Media Association group. While he was out walking one day, a car pulled up next to him at the curb and a uniformed KGB officer jumped out and scowled, "Get in the car!" The scholar responded just like children are taught when strangers try to pick them up: He just said "No." The officer repeated his command but soon drove off. If it had been a serious arrest, there would have been more than one officer and they would have grabbed him physically. I think they just wanted to let him know they knew who he was and that he was being watched -- what the Mafia would call "a friendly warning."

Before we left the United States, a source told us that one of our guides would be KGB. That must have been Alex, a sour, hardline party member who told us on more than one occasion that we were the most anti-Soviet group he ever had the displeasure to meet. Our other guide, Igor, ignored ideology and politics and seemed to enjoy our company.

Bill

Gertz of The Washington Times, center right, asks a question in a

meeting with the top editors of Novesti News Agency.

Question: Who did you officially meet with over there?

We met journalists from Izvestia newspaper and TASS and Novesti news agencies. In addition, we met officials of the Defense Ministry, the Foreign Ministry, and the Academy of Sciences. We also always meet a certain number of Soviet dissidents, contacted before the trip through friends in the United States.

On previous tours, Soviet dissidents whom we had arranged to meet were sometimes "warned" about associating with us, the way the Ukrainian scholar was. They were not arrested, just searched and hassled. It made some of them reconsider meeting with our participants and made those who did meet with us less free to express themselves fully.

At our official meetings with Soviet journalists and government representatives, the comments and questions our participants posed were so focused and so filled with damning information that our Soviet hosts spent most of the time trying to dodge them. When they got a question they couldn't handle, their standard behavior was either to pretend the question wasn't asked and simply change topics, or to counter with an accusation of their own, or to reply with a totally irrelevant answer.

For example, in our discussion with the deputy editor of Izvestia, Arnold Beichman asked, "You talk about your new policy of glasnost -- 'openness; but that implies that at one time you were not open. What were you hiding before? Are you saying that you've been less than perfect in the past?" The editor replied, "We do not consider our history a failure. My mother was born in a small village. Out of every 100 Germans killed in World War II, 85 were killed on the Russian front. We have created a new society and we are still doing it. The aggressiveness of the West is responsible for many of our difficulties in the past." That's how he answered the question! After a while you felt the room was spinning with those kinds of answers. Particularly maddening for Westerners is the fondness these institutional atheists have for answering our criticisms with Bible quotes, especially the one about how we must not harp on the mote in their eye before dealing with the logjam in our own.

Question: Does anyone challenge them and say, "You don't believe in the Bible, so why do you quote it?"

I did once, on a previous visit, and the reply was, "Must I be a Muslim to quote Mohammed or a black to laugh at the humor of Eddie Murphy?" To them, truth and logic are nothing more than tools, toys if you will -- certainly not things they live by or adhere to in any way.

A

session with the Union of Journalists. The WMA tour leader,

Ambassador James Theberge, who was a U.S. ambassador to Nicaragua and

Chile, sits center left (with glasses). To his right is John Robbins,

WMA projects coordinator. The man with his hands folded is Igor, the

group's friendly Soviet guide.

Question: Were you able to walk around on your own, apart from the official tour schedule?

Yes, and in fact we encourage it. The Soviet tourist guides learned long ago that people from free countries don't at all like being told you can't take a bus by yourself or visit a coffee shop on your own, so they now make a big thing of announcing which buses go from the hotel to various points of interest. Constraints have loosened up a bit for them as well. A few years ago the guides from Intourist (the government tourist agency) were required to make nightly reports on who strayed from the group, who met a Soviet citizen, etc. Now they only have to make note of a tourist who is fluent in Russian or is conspicuously absent or suspicious.

The journalists on our tour went everywhere. Many of them had prearranged interviews with officials, priests, and private citizens. There is a growing segment of Soviet people who have a sort of hobby of meeting American tourists, for reasons ranging from innocently wanting to practice English or trade something for a Billy Joel tape, to those who make their living off illegal dollar-to-ruble exchanges.

They like Americans, despite the fact that Soviet propaganda depicts Americans with long pointed teeth hanging down like tangs in the shape of missiles. The government's "ugly American" line, like the banners and slogans they see everywhere, is not actually absorbed by the people. It has become a cliché that Soviet youth want American music, sneakers, and blue jeans, but more than before, it seems that recently they want to have an American friend as well.

But it is still a risky endeavor. Some Soviet citizens who struck up conversations with us on the street were quite nervous because chances were good they were being watched or that they would be searched or hassled after leaving us. I had a friend who told me to write him at his office, rather than his home, because, if he gets the letter at work, he said, they know he is not trying to hide anything. Occasionally on the street I would notice some young person watching us from several feet away, as if he wanted to approach and speak but was unable to overcome his shyness.

In a bookstore in Leningrad, a man in his mid-30s whose field is sports medicine introduced himself to me. He collected books of beautiful paintings and was hoping I had one I could send him in exchange for one of his. We went to his apartment, which was at the top of several unlit flights of stairs in a building that had received nothing but the most rudimentary maintenance.

His apartment, like others I have seen, was sparsely furnished, with one small, naked light bulb barely lighting the gloomy hallway. There, four families shared a common kitchen and bathroom, and each family had one room of its own for sleeping, studying, and everything else.

We left our shoes outside his room and entered his world -- a humbly furnished but brightly lit and immaculately clean room. The window was covered, protecting the ambiance from any intrusion. On the walls were rows and rows of art books and classical literature in Russian and English. On a table by the couch was a portable stereo cassette player and two or three dozen tapes, some originals and some bootleg copies, ranging from classical to heavy metal. He said most all the items had been received as gifts or trades with foreigners he had met.

Like many Soviet people I met there, he was unhesitatingly patriotic, but his patriotism was directed toward "my country" or an unspoken "Mother Russia'." He seemed to distance himself from all aspects of the political USSR. I have met many in the Soviet Union who cling to an apolitical outlook as though it were a refuge.

Later, he insisted on buying me lunch at a typical Soviet restaurant. There's no menu. You just approach the counter and order "lunch." When it's ready (usually meat and vegetables), you fetch it and take it to your table. No decor. No waiters. No service with a smile. And when you leave, no "y'all come back."

The numbing lack of personality in restaurants is one aspect that has the possibility of changing. This year, for the first time, the authorities have allowed a restaurant to open under the private ownership of five families who pooled their rubles and went into business. When you walk into this restaurant, all the things you normally take for granted in a restaurant really stand out -- attractive displays of food, soft lights, a live piano and violin duo, courteous waiters, even a maître d. It was wonderful, but expensive by Russian standards, and we even had to make reservations. Before they started taking reservations, the lines used to stretch most of the way down the length of a block,

Tom

Ward gives a lecture on freedom of religion to the tour participants.

The only place they could meet among themselves was in the hotel

basement, the employees' meeting and indoctrination room.

Question: Is the black market pretty active?

It's the only excitement in the whole country. The official exchange rate is $1.25 for one ruble. But the exchange rate offered by the teenagers outside the door of our hotel, the real rate, is six rubles for one dollar. A Westerner can be spotted in a crowd a block away by any native. ("It's because your clothes are so nice." a girl told me, indicating my 10-year-old suit.)

Even if you have a lot of rubles, there isn't much you can legally buy with them. When I put a couple of rubles in my bellhop's hand he only had eyes for the two packs of Marlboros on my dresser. "Cigarettes is better," he said with a smile. I handed him the cigarettes and he handed me back the rubles. I always pick up a couple cartons of Marlboros in Helsinki before entering the USSR, as it is the prestige medium of exchange.

Actually, I never met so many capitalists as I have seen in the Soviet Union. If there is a shoe sale, people get in line and buy as many pairs as the limit allows and then sell them illegally at a profit. In order to survive in the Soviet Union you have to do this. Factory workers are willing to go to rallies and look like they're supporting the Revolution because they are paid five rubles if they do. If they carry a placard with a picture of Lenin they get 10 rubles. Nobody feels respect for the government; they just try to get whatever they can, in whatever way they can.

Question: Is the cult of Lenin still prevalent?

Lenin is still number one, and the line to see his waxen body still stretches from the front door of the tomb, across Red Square, and down the street. Everything is Lenin, Lenin, Lenin.

His face is everywhere. He smiles impishly and twinkly-eyed in a picture surrounded by cherubic young pioneers. Ubiquitous statues depict him exhorting the masses or gazing resolutely into the socialist future. He is referred to in messianic terms from an oft-quoted Russian poet: "Lenin lived. Lenin died. Lenin will live again" When we visited the Young Pioneers Camp, an after-school youth club, there was a statue of Lenin with a bowl in front of it and a bucket of flowers beside it. When people come in they take a flower and place it in the bowl in front of Lenin.

Bill

Lay and Larry Moffitt rejoice after their Il Jeung prayer in

Leningrad.

Question: Nowadays we hear the term perestroika as a new domestic Soviet policy. What exactly does it mean?

Perestroika means "restructuring," and involves everything from creating economic incentives for workers to even allowing criticism of management. Generally, it means allowing more worker participation in government decisions. Arnold Beichman says it is a total sham, that it is simply detente by another name, another lullaby sung to the West. I agree. The Soviets still want to take over the world, they just want their people to produce more so they can get out of debt and still keep ahead of us in weapons. If the Soviets can get Americans thinking that the USSR no longer has designs for world conquest, as President Reagan said, then the U.S. Congress will cut off funding for SDI and other defense measures, which will free the Soviet Union to spend more money domestically.

Izvestia told Bill Gertz, who represented The Washington Times, that if he wrote an article about his view of the Soviet Union, they would print it in full. They probably will, because the Soviet Union right now is desperate to get cooperation from the West, especially conservatives, to lull them to sleep. I don't know about the future, but so far I think their success in deceiving the United States with this strategy has exceeded their wildest dreams.

But perestroika may also be the Soviet Union's biggest mistake: History teaches that revolutions usually happen not when people are the most oppressed but when things start to get just a bit better and the government is unable to control the energy of change. Sovietologists like Arnold Beichman disagree, saying the Soviet Union has never paid the slightest bit of attention to public dissatisfaction, and whatever expectations on the part of the Russian people are created by this new wave will either be ignored or put down with force.

In the past, the people never took the government seriously with its talk about a "worker's utopia," but for some reason, when Gorbachev speaks this time that "we need democracy like we need air," people believe it and allow themselves to get very excited about it. If the people's expectations continue to rise, they may be so shocked and outraged when authorities begin to clamp down again that the Soviet government may no longer be able to get away with ignoring public opinion as it has for 70 years.

Here is an example of the growing willingness to express opposition.

One of the stops on our tour was the "Friendship House famous among tourists as the place where the government hauls out a couple of professors and a dozen "typical" students to hold a discussion on international affairs. In past years the students would be more than eager to criticize U.S. policy and daily life, but this time it was different. Tom Ward asked if high school and college students can read works other than those of Marx and Lenin and commentaries on such. The professor answered, "Of course However, a student stood up and said, "That simply is not true." There was a long silence, and the student continued, his emotion building. "We want to read Freud and Nietzsche in the original texts, but all we get is a paragraph telling us that Freud said such-and-such, but was wrong. We want to read for ourselves"

The professor angrily silenced the youth with an abrupt "Spasiba!" ("Thank you"), then tried to explain that the student was referring to something in the past and that things were different today. The now silent student, however, still glared with an anger that was quite fresh.

As we broke up, a guest quietly asked one of the students if there would be any retribution toward his rebellious colleague and was told: "I'm sure he won't be invited back again, but don't worry about him, because this kind of thing is happening all over the Soviet Union now"

I think this incident accurately portrays the dilemma of the Soviet Union regarding perestroika.

Question: How does atheism figure into the lives of the people in general?

Atheism is institutionalized. It's taught from the very beginning. One example is the Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism in Leningrad, not part of the normal Intourist package unless you specifically request it. Built in what used to be the Cathedral of the Virgin of Kazan, the museum shows how religion evolved from shamanism and primitive religions up through Judeo-Christianity and how it all will eventually evolve into communism.

Bill Lay asked the guide, 'After 70 years of communism, why is there still any religion in the Soviet Union at all?" The guide received it as a question from a fellow atheist and almost apologetically admitted they had not succeeded in eradicating religion in the USSR. She gave the following reasons: World War II (in times of great stress people often lean on religion), the Voice of America radio propaganda keeping religion alive, and people using religion as a crutch in overcoming personal problems.

Question: Did you visit any churches?

We went to a few of what Intourist calls "functioning churches" -- such as the famous Russian Orthodox monastery at Zagorsk, where members of the czar's family had attended services. The priests insisted that their parishioners were perfectly free to practice their faith, and that the government even printed their Bibles. They claimed not to know whether their churches were growing or shrinking in membership, or whether religious conversions seemed to be increasing or decreasing, information normally foremost in the mind of every minister in the world. Those in our group who became frustrated with the lack of straight answers needed to be reminded that the priests must stay behind to baptize and minister after the journalists leave, and if lying to reporters is part of the rent that must be paid for an official "functioning church" to remain functioning, so be it.

Question: What about sincere religious faith?

When we said we wanted to go to a Baptist church, our tour guide somehow gave us the wrong address. However, while looking for it, I happened to turn into an archway leading to what looked like someone's ordinary courtyard. Surprisingly, it felt wonderful standing in there, but because we didn't see anything that looked like a church, we left. The next day, I felt moved to return to that courtyard, and sure enough, we discovered a real Baptist service being held inside. It was so alive! The room was filled wall-to-wall with people who had arrived up to two hours before the service -- young people and old. The whole two-hour service was heartfelt testimonies, repentance, and prayer. They had a choir that was just vibrant. It was the only place in the Soviet Union where I actually felt God's spirit. And it was strong!

That religiosity is something that just can't be repressed. Even within the Kremlin, where there are several churches preserved as museums, you see old women kissing the icons of the saints or the crucifixes and crying fervent prayers to Jesus. The people always pray standing up; in fact, they think it is an insult to God that American people pray sitting down. When they declare for Christ, many of them will also tell their employers, "I became a Christian this week. I want to live for Christ. I'm telling you this so you can, too." Sometimes they lose their jobs because of this and can't get hired again. God truly, truly loves those people.

Question: What was the participants' evaluation of the conference?

They were all surprised at how dreadful the Soviet Union was. On every tour we've had, when we land in Finland after coming out of the Soviet Union there is applause, giddy laughter, and tremendous joy, like a child's joy. After 10 days there you really feel the oppression that the people live under. If those journalists were suddenly told they had to turn around and go back and actually become a resident of the USSR, I think you'd have everybody slitting their wrists! What we hope the tour does is to make people really think, "What if I lived here? What if this were my life?"

In a sense, the tour itself is kind of a non-stop testimony to Father. They see the reality of Soviet life and they see our members, and they sense something is very different and special about us. So many of the participants would come to me privately and ask, in a very sincere way, "Why does Rev. Moon sponsor these trips? What exactly does Rev. Moon believe, anyway?" And I tell them, "Rev. Moon wants more than anything else in the world to save the Soviet people. He loves them even more than he loves you and me, because he loves the people that God loves, and God loves those who are the most suffering and oppressed. Rev. Moon wants to tell everybody about how communism crushes people's spirits and destroys their lives, their hopes, and their dignity" This makes these journalists think. Many times they say afterward, "If there is anything I can do for Rev. Moon, please let me know"

At the end of the tour we asked all the participants to sign a beautiful Russian book of ocean paintings to give True Parents. Inside it said: "To Rev. and Mrs. Moon -- with deepest appreciation for sponsoring this fact-finding tour, for giving us a chance to learn more about the Soviet Union and its people" They were as eager as school kids to sign it, all of them wanting to put their name as close to the top as possible. To me that was a sign that they all wanted to be as close as possible to Father.

Question: What is it like spiritually to be in the Soviet Union?

It's like being in hell. The Unification Church members decided to do a four-hour Il Jeung prayer in each of the three cities we visited. We started in Moscow, then Samarkand, and finally in Leningrad. The prayers were never easy, and to me it seemed to become harder to break through each time, rather than easier.

At first we thought we shouldn't pray in our hotel rooms because we had experienced in the past that they were often bugged. But finally we decided to pray there anyway, figuring Satan already knows why we came and what our feelings about communism are.

Our last Il Jeung prayer ended outside at the seawall in Leningrad. The moon was full and bright and the sea crashed against the barrier, driven by a freezing wind. We shouted our closing prayers and our Manseis. At that moment, after our third Il Jeung prayer in a week, we felt stronger than the powerful satanic spirit of the entire country.